Vinni Lucherini, Università di Napoli Federico II

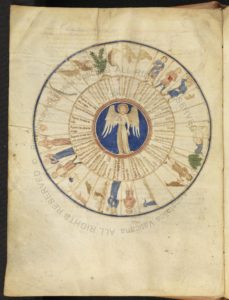

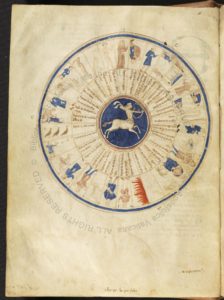

In Late Romanesque Europe, while the literary and philosophical expressions of what is known as the “12th century Renaissance” were developing, images of the signs of the astrological zodiac (which had already flourished in the Carolingian period) invaded the mosaic pavements of churches, and also appeared sculpted in portals and on capitals, or painted on the walls of many religious buildings.

In Late Romanesque Europe, while the literary and philosophical expressions of what is known as the “12th century Renaissance” were developing, images of the signs of the astrological zodiac (which had already flourished in the Carolingian period) invaded the mosaic pavements of churches, and also appeared sculpted in portals and on capitals, or painted on the walls of many religious buildings.

In illuminated manuscripts, representations of stars and diagrams abound. At the end of the 12th century, the translation into Latin of the works of the Greek astronomer Ptolemy (Ptolemaeus of Thebaid, born around 100 and died around 170), in particular the Almagest (a treatise on mathematical astronomy) and the Tetrabiblos (or Quadripartitum, on astrology), transmitted mainly through Arabic sources, gave a new scientific focus to astronomy, one of the four liberal arts of the quadrivium.

In Norman Palermo, for example, the Almageste was translated directly from Greek, shortly after 1158, on the basis of a copy sent to King William I of Sicily by the Byzantine emperor Manuel I Comnenus. At the beginning of the 13th century, there was a strong interest in theoretical and practical astronomical texts in other princely courts in southern Europe, such as those of Emperor Frederick II and King Alfonso the Wise of Castile.

In Norman Palermo, for example, the Almageste was translated directly from Greek, shortly after 1158, on the basis of a copy sent to King William I of Sicily by the Byzantine emperor Manuel I Comnenus. At the beginning of the 13th century, there was a strong interest in theoretical and practical astronomical texts in other princely courts in southern Europe, such as those of Emperor Frederick II and King Alfonso the Wise of Castile.

The question to be addressed here is the extent to which astronomical manuscripts commissioned by rulers or produced in the intellectual circles of their courts can be considered instruments of power.